Strongly Connected Components Algorithm Optimized

- Introduction

- Strongly Connected Components

- Kosaraju’s Algorithm

- Implementation and Optimization

- Stack Overflow !!

- Summary

- References

Introduction

This post is inspired by the online course, Graph Search, Shortest Paths, and Data Structures, available from Coursera and Stanford University. We discussed what Strongly Connected Component (SCC) is and how to detect them using Kosaraju’s algorithm. One assignment is to implement the algorithm to tackle a large directed graph with over 800,000 nodes and 5,000,000 edges. This post shows how I solve the problem from a naive to the optimized solution.

In a nut shell, this post discusses:

- Concept of SCC;

- Pseudocode for Kosaraju’s algorithm;

- Implementation and optimization of the implementation;

Strongly Connected Components

What is an strongly connected component? A pair of vertices, u and v, is strongly connected if there exists a path from u to v and a path from v to u. An SCC is a subgraph of a directed graph that is strongly connected and at the same time is maximal with this property.

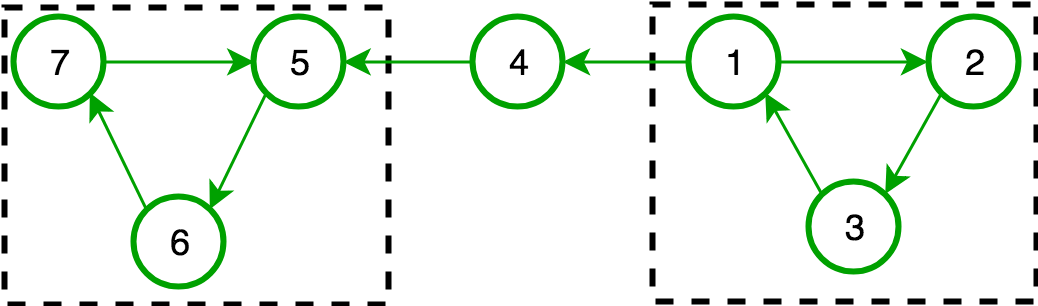

Consider the following directed graph with 7 vertices.

There are 2 SCCs in this graph grouped by dashed lines, G1 = {1,2,3} and G2 = {5,6,7}. Take G1 as an example, nodes 1, 2, and 3 are strongly connected because there exists a path from each of them to the rest of the nodes in this subgraph (1 -> 2, 2 -> 3, 3 -> 1). At the same time, no nodes in the rest of the subgraph {4,5,6,7} have this property. There is no path from 4 to 1 for instance. Therefore, subgraph {1,2,3} can be identified as an SCC.

So why does SCC matter? There are generally two main reasons. First, SCCs are helpful for clustering a graph. Some part of the graph is more closely related compared with others, and this property is very important in a variety of applications, like social network and transportation network analysis. Second, it is useful for identifying bottlenecks of a graph. For example, after identifying two SCCs in the above graph, paths 1 -> 4 and 4 -> 5 can be the bottlenecks of this graph. If this is a computer network, nodes 1, 4, and 5 should be equipped with larger bandwidth to maintain the speed of network communication.

The concept of SCC is so important for learning the structure of a grpah. Have you ever wondered what the Internet looks like? Since the Internet simply consists of a huge amount of links, it is essentially a complicated directed graph. Broder et al. have found out in 2000 that the structured of the Web 2.0 resembles a bow tie with the knot being a huge SCC depicted in the figure above. What remains in the rest of the structure? I recommend you read the excellent paper!

That brings us to the next question: how do we find SCCs of a graph?

Intuitively, I imagine an SCC as a maximized loop. With that I mean the maximized loop can be a single loop circle, or it can be a set of interconnected loops. The question then becomes how we find the maximized loops in a graph. A loop means starting from a vertex, say node 1, there exists a path to itself, which would be 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 1 in this case. This task is actually a perfect application for Depth-First Search (DFS).

But how do we use DFS to search for SCCs in a graph? This is the last but the most important question. For example, if we start a DFS from node 7 we can find an SCC {7, 6, 5}. If we start a DFS from node 4 we cannot find any SCC. If we start a DFS from node 1 we might or might not find an SCC. Therefore, If we start DFS at correct palces and in the correct order, we will be able to find SCCs. Otherwise, no information can be provided from the search.

Kosaraju’s Algorithm

Kosaraju’s algorithm is designed to find SCCs of a graph. In short, the algorithm run DFS of the graph two times. The first DFS of the graph identifies a “magic order” of the each node, and the second DFS of the graph is done using this “magic order”. At the end of the algorithm, each node will be assigned with a leader node, and nodes with the same leader nodes is an SCC. The algorithm complexity is O(m + n). m is the number of edges and n is the number of vertices.

The Kosaraju’s algorithm pseudocode is shown below.

function find_SCC_Kosaraju (G);

Input: a directed graph G

Output: node leaders

Global vector leader to keep track of node leaders

Global vector finishing to keep track of finishing time of nodes

Let G_rev = the reversed graph of G

Run DFS_loop on G_rev

Rename nodes to its finishing time

Run DFS_loop on G

The DFS_loop function pseudocode is shown below.

function DFS_loop (G);

Input: a directed grpah G

Global variable t = 0 // # of nodes processed so far

Global variable s = NULL // Current leader

For i = biggest node label to smallest

- if i not explored

- s := i

- DFS (G, i)

The DFS function pseudocode is shown below.

function DFS (G, i);

Input: a directed grpah G, current node i

Mark i as explore

Set leader[i] := s

For each arc(i, j) in G

- if j not explored

- DFS (G, j)

t++

set finishing[i] := t

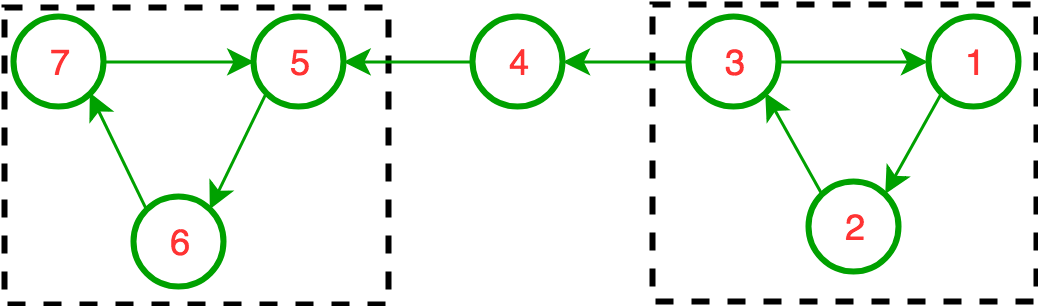

Use the graph with 7 nodes as an example. The algorithm starts the DFS from the node 7 on the reversed graph. The visiting order is 7 -> 6 -> 5 -> 4 -> 1 -> 3 -> 2. Therefore, node 2 is the first to finish, being assigned with 1 for finishing time. Then it is 3, 1, and so on. After renaming the nodes to their finishing time. The original graph becomes the following. Please note that the node label is changed to its finishing time, therefore being labeled with a different color. The label is not its original label.

The second DFS of the graph again starts with the biggest label to the smallest label. Now things become straightforward. For example, DFS from node 7 will find the first SCC {7, 5, 6}, and these nodes will be assigned leader 7; DFS from node 6 will finish immediately become node 7 has already been visited; DFS from 3 will find the second SCC {3, 1, 2}, and these nodes will be assigned leader 3.

You may also add another post processing step to convert the leader node label to its original label.

Implementation and Optimization

Now that we already have this blazingly fast algorithm, why should we worry about optimization? Reality is that algorithm complexity is not everything, and implementation matters.

I have bundled all my codes and data into an R package. You can find it here. Guide on installation directly from the repository is included in the README file. If you want to run the experiment, please use the script compare_methods.R

The machie I’m using is a MacBook Air (early 2015) with dual 2.2 GHz Intel Core i7. It has 8 GB 1600 MHz DDR3 memory.

I first implemented the algorihtm according to the pseudo code, as shown in file SCC_solution_1.cpp. The DFS function if recursive as shown below.

// This function is a recursive function for DFS.

void DFS_recursive(

const vector<value_type> & tails,

const vector<value_type> & heads,

value_type node, value_type leader,

SCC & scc) {

value_type index, next_node;

// Mark the cuurect node as explored

scc.explored.at(node - 1) = true;

// Set the leader of this current node

scc.leaders.at(node - 1) = leader;

auto it = find(tails.begin(), tails.end(), node);

while (it != tails.end()) {

index = distance(tails.begin(), it);

next_node = heads.at(index);

if (!scc.explored.at(next_node - 1)) {

DFS_recursive(tails, heads, next_node, leader, scc);

}

it = find(it+1, tails.end(), node);

}

// Record the finishing time

scc.counter++;

scc.finishings.at(node - 1) = scc.counter;

}

First of all, this solution passes the correctness test because it can find the same number of SCCs as the igraph package. But the recursive approach becomes very slow when dealing with larger data set. For example, the following profiling results come from the data set edge_list_wiki-vote. This data set contains 103689 edges and 7115 nodes.

# Time profiling of the igraph

user system elapsed

0.072 0.009 0.081

# Time profiling of the SCC_solution_1

user system elapsed

0.658 0.003 0.666

Another exmpale from the data edge_list_twitter. This data set ocntains 2420744 edges and 81306 nodes.

# Time profiling of the igraph

user system elapsed

0.873 0.100 0.987

# Time profiling of the SCC_solution_1

user system elapsed

209.677 0.913 212.548

This is not impressive at all. Although recursive calls are relatively easy to write, it tends to generate lots of functions calls therefore requiring constantly call stack resizing and memory caching. In this case, the layers of recursive calls will be linear to the length of a path. This can potentially be very large. So can we avoid using recursive calls?

When using recursive calls, the operating system manages a call stack for us. Theoretically, we can just manage our own stack, and convert the recursive function into a iterative function. My first optimization is in file SCC_solution_2.cpp.

// This function is not recursive, but uses iterative

// approach and manages the nodes to visit using a

// stack data structure.

//

void DFS_nonrecursive(

const vector<value_type> & tails,

const vector<value_type> & heads,

value_type node, value_type leader,

SCC & scc) {

// Create a stack to keep track of nodes

stack<value_type> nodes_to_visit;

if (!scc.explored.at(node - 1)) {

nodes_to_visit.push(node);

}

while(!nodes_to_visit.empty()) {

bool finished = true;

node = nodes_to_visit.top();

if (!scc.explored.at(node - 1)) {

// Mark the next node as visited

scc.explored.at(node - 1) = true;

scc.leaders.at(node - 1) = leader;

// Find the elements from the right beginning

// so that the exact same finishing time can

// be generated with the recursive method

//

auto it = find(tails.rbegin(), tails.rend(), node);

while (it != tails.rend()) {

// size_t index = distance(tails.begin(), it);

size_t index = distance(it+1, tails.rend());

value_type next_node = heads.at(index);

if (!scc.explored.at(next_node - 1)) {

nodes_to_visit.push(next_node);

// This node introduces new child node

// so thie node will be kept in the stack

//

finished = false;

}

it = find(it + 1, tails.rend(), node);

}

}

if (finished) {

// If the node does not introduce any new children

nodes_to_visit.pop();

if (scc.finishings.at(node - 1) == 0) {

// If the node finishing time has not been calculated yet

scc.counter = scc.counter + 1;

scc.finishings[node-1] = scc.counter;

}

}

}

}

This function manages its own stack variable nodes_to_visit to keep track of nodes that are yet to be visited. However, by having this changed, I need to carefully define when to increment the finishing time. I introduced a vairable to monitor whether a node has ever added any new child nodes. If a node does not add any new child notes, I increment the finishing time by 1. This can happen in two situations:

- The node is a sinking node. Then of course, this node is finished. We should increment the finishing time.

- All children of the node is already visitied. Then this node is also finished. We should increment the finishing time.

The profiling result is shown below. The test data set is edge_list_twitter.

method user system elapsed

igraph 0.800 0.092 0.902

SCC_solution_1 211.795 1.108 215.784

SCC_solution_2 181.296 0.781 183.776

Still not very impressive. Then I realized I was being very careless by doing the following in DFS_nonrecursive function.

auto it = find(tails.rbegin(), tails.rend(), node);

while (it != tails.rend()) {

...

it = find(it + 1, tails.rend(), node);

}

I’m finding node children by traversing the graph. This makes the algorithm complexity quadratic, rather linear! I need an adjacency list of the graph. So I introduced another function in data pre-processing step to generate an adjacency list first, and then it will be used in the Depth First Search function. SCC_solution_4.cpp is an improved version of SCC_solution_1.cpp and SCC_solution_3.cpp is an improved version of SCC_solution_2.cpp.

The profiling result is shown below. The test data set is edge_list_twitter.

method user system elapsed

igraph 0.805 0.084 0.901

SCC_solution_2 182.850 0.835 185.385

SCC_solution_3 0.681 0.030 0.717

SCC_solution_4 0.673 0.025 0.700

Very impressive! But I’m still curious about how the time is spent by the algorithm. If you set verbose to TRUE, you should be able to see the following standout output from the SCC_solution_3.

Generate adjacency list ...

Processing the 1st DFS loop ...

Rename nodes by the finishing time ...

Generate adjacency list ...

Processing the 2nd DFS loop ...

Preprocessing: 0.392 s(57.2%)

Generating adjacency list: 0.0942 s(13.8%)

Computing finishing times: 0.0465 s(6.79%)

Renaming nodes: 0.00483 s(0.705%)

Generating adjacency list: 0.103 s(15%)

Computing the leaders: 0.147 s(21.5%)

Total time: 0.685 s(100%)

Stack Overflow !!

Recall that SCC_solution_4 uses the recursive method for depth-first search and SCC_solution_3 maintains a stack by the function itself. There is a possibility that the system-maintained stack is too small and too many recursive calls are created due to a very long path (or a very deep search), for example, a path with 1,000,000 nodes.

In the fifth test case, a graph with only one path is created. This path has 1,000,000 nodes. Therefore SCC_solution_4 will have to create as many recursive calls. This will create problems like below if you run the solution.

You can either increase the maximum number of recursive calls by increase the stack size when compiling the package, or, as I mentioned before, maintain a stack by yourself. The same test data set runs fine with SCC_solution_3.

method user system elapsed

igraph 1.208 0.116 1.348

SCC_solution_3 1.653 0.076 1.739

If ,’unfortunately’, the script runs without a problem even for SCC_solution_4 on your computer, you can still reproduce this situation by prolong the path. Use the function get_maximum_recursive_calls() from the WeimingSCC package to know how many recursive calls can be created for your program. Change the nrows on line 86 in compare_methods.R to make it bigger than the maximum.

Summary

My biggest take-away from this learning experience is that a fast algorithm depends on both the complexity and the implementation. We use math to analyze complexity, and profiling to analyze implementation. Performance of the program is very important in graph analysis because we never have problems find a graph that is massive, for example, the Internet, transportation, and social networks. So ideas and hands-on both play an important role.

References

- Broder, Andrei, et al. “Graph structure in the web.” Computer networks 33.1-6 (2000): 309-320.

- Geeks for geeks explanation on SCC